Article & photos by Murphy Shewchuk Once threatened, a BC marshland now has a future. British Columbia's roller-coaster beauty dips, climbs and swoops from one spell-binding scene to another. Despite the distractions, each year 20,000 visitors find their way off Crowsnest Highway 3 to explore the rich wetlands of the Creston Valley. From the west, Crowsnest Highway makes a long, steep downhill run from the 1,774-metre summit of the Kootenay skyway to one of the most productive wetlands in the interior. The downhill run is symbolic of the fate that the Creston Marsh faced for more than half a century. The Creston Valley story starts with the first trickle of the Kootenay River high in the Rocky Mountains southeast of Golden. The river carves a meandering, international route southward into Montana before making a wide loop through Idaho and northward into BC. The Kootenay River continues northward to Kootenay Lake before draining into the Columbia River near Castlegar. Through thousands of years of meandering, the river created a 70-kilometre long swamp, eight to ten kilometres wide, that extended from Bonner's Ferry, Idaho, past Creston's doorstep, to Kootenay Lake. Waterfowl congregated here in great numbers, especially in spring and fall. First Nations people followed the last retreating ice age into the region nearly ten thousand years ago, living off the wildlife and adapting their way of life to the marsh. When Europeans came to western North America, Fur Trader David Thompson first explored the Kootenay system between 1807 and 1811. Gold seekers and settlers followed the fur traders into the region. The Creston marshes served the Kootenay Indians and complicated the building of the Dewdney Trail to the Kootenay goldfields. However, it wasn't until the mid-1880's that anyone actually tried to do anything about the marsh itself. It was then that W.A. Baillie-Grohman began his Canal Flats project north of Cranbrook. Baillie-Grohman intended to divert the upper Kootenay River into the Columbia River, in an effort to reduce downstream flooding on the Creston Marsh. Unfortunately for him the Canadian Pacific Railway, whose tracks along the Columbia would have faced flooding, had the project halted. Baillie-Grohman pursued his plan to reclaim the Creston Marshes for more than a decade before returning to England in 1898, broke and disheartened. Although Baillie-Grohman gave up, the threat to the Creston marshes didn't end there. Others picked up the shovel where he dropped it. By 1927, the Creston Reclamation Co. Ltd. was intent on "opening up every acre of these 30,000 acres on each side of the (border)line."

From the first reclamation efforts in 1884 until the West Kootenay Power expansion hearings in 1942, the marshes were repeatedly under siege. They would almost certainly have been lost had the Kootenay not been an international river. However, presentations by Nelson resident J.J. (Mickey) McEwen prompted the International Joint Commission (IJC) to postpone their decision until wildlife studies could be completed. Dr. James Munro of the Canadian Wildlife Service (CWS) was commissioned to study the marsh. When he presented his findings in November, 1947, the stage was set for a major confrontation. On one side were provincial and federal government departments and a host of business groups supporting further reclamation. On the side of wildlife were the CWS, Ducks Unlimited and numerous rod and gun clubs from BC and Idaho. The heightened controversy resulted in more delays. Then, in August 1949, the IJC gave the Creston Reclamation Company permission to dike off 3,200 acres on the south end of Duck Lake. The reclamation company later decided that the land allotment wasn't adequate and controversy erupted again. Hearings followed in 1950 and the IJC approved a plan that would see the Creston Reclamation Company drain the south end of Duck Lake and renounce all claims for the remainder of the lake. A year or two later, Dr. Munro issued his report detailing a plan for the development of a Duck Lake wildlife management project. Tempers cooled. Then in 1954 the Duck Lake Dyking District applied for an additional 1,500 acres of marshland -- and the fight was on again. Mickey McEwen had led the battle to save the marsh for more than a decade and was wearing down. Frank Shannon, a geologist at the nearby Bluebell Mine, accepted the challenge, beginning a battle that would consume him for more than a decade.

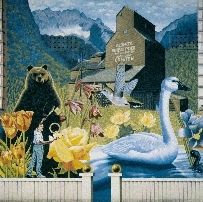

Hearings, studies and surveys continued for six more years before the Creston Valley Wildlife Management Act was passed in March, 1968. "We all breathed a sigh of relief," says Frank Shannon. "It was finally over after 26 years. Through those years there were many, many people who worked hard and long to make this become a reality." The formal creation of the wildlife management area in 1968 was the end of the war to save the marsh. However, it was only the beginning of the battle to turn the flood plain into productive wildlife and waterfowl habitat. With the support of Ducks Unlimited, wildlife groups and various government grants, The dikes now create much-needed wildlife habitat by managing water levels. With almost 17,000 acres of priceless wetlands under their protection, the Creston Valley Wildlife Management Authority (CVWMA) faces a monumental task. So far, despite funding and weather setbacks, they have been successful. The number of nesting duck species has more than doubled. The nesting colonies that started in small, isolated areas have spread throughout the 7,000 acre habitat. A communal heronry of more than 100 nests has been identified, while the resident population of eagles and ospreys continues to grow. Duck Lake, the focal point of much of the battle to save the marsh, is not only home to waterfowl. A whole range of wildlife from leopard frogs and western painted turtles, to fish, to playful river otters and majestic elk make the lake part of their home. In fact, where some once visualized cultivated land, a significant bass recreational fishery has developed, attracting fishermen from western Canada and the U.S. People benefit in other ways, too. Visitors to the Creston Valley Wildlife Interpretation Centre, situated in the Corn Creek Marsh, number roughly 20,000 a year. In exchange for the thrill of watching and photographing wildlife, being scolded by a red-winged blackbird or tramping the dike-top trails, they contribute to the economy of Creston and Western Canada.

When Mickey McEwen began the battle to save the Creston marshes nearly sixty years ago, it's doubtful he envisioned a catwalk across a turtle-inhabited pond. Likewise, when Jim Munro added his opposition to reclamation during the war years, he may not have been thinking about university students doing graduate studies. And when Frank Shannon picked up the torch in 1954, it is almost certain that he didn't expect to carry it for 33 years. Even men of vision cannot reliably predict the future, but McEwen, Munro and Shannon deserve the gratitude of men and wildlife alike. Their foresight and tenacity has helped preserve the priceless living gem that is the Creston marsh. Copyright © 1999-2009 Murphy O. Shewchuk www.murphyshewchuk.com Be sure to read other articles by Murphy Shewchuk in the BC Adventure Network |